Part of our Home Assistant (HA) setup uses the Companion Mobile App for easy remote control and to collect data from our devices. The main tracked item is the phone’s location, so HA can tell if we’re home or not, and currently I only use it to change how some lighting automations work.

I also have HA set up to log all device state data (switches, outlets, climate sensors, power consumption) to a local instance of InfluxDB, and then have Grafana installed so I can visualize this data.

My original use for this was long-term logging of temperature and humidity sensor data — which is neat to see — but as I’ve experimented with graphing things like mains voltage. This was neat because it made it easy to see things like how voltage drops and becomes erratic during summertime cooling periods. And showed that grid voltage jumped up by ~2VAC in March 2025, around which time I recall DTE doing utility work on the grid just north of our house. (Yes, evidence of them improving things locally.)

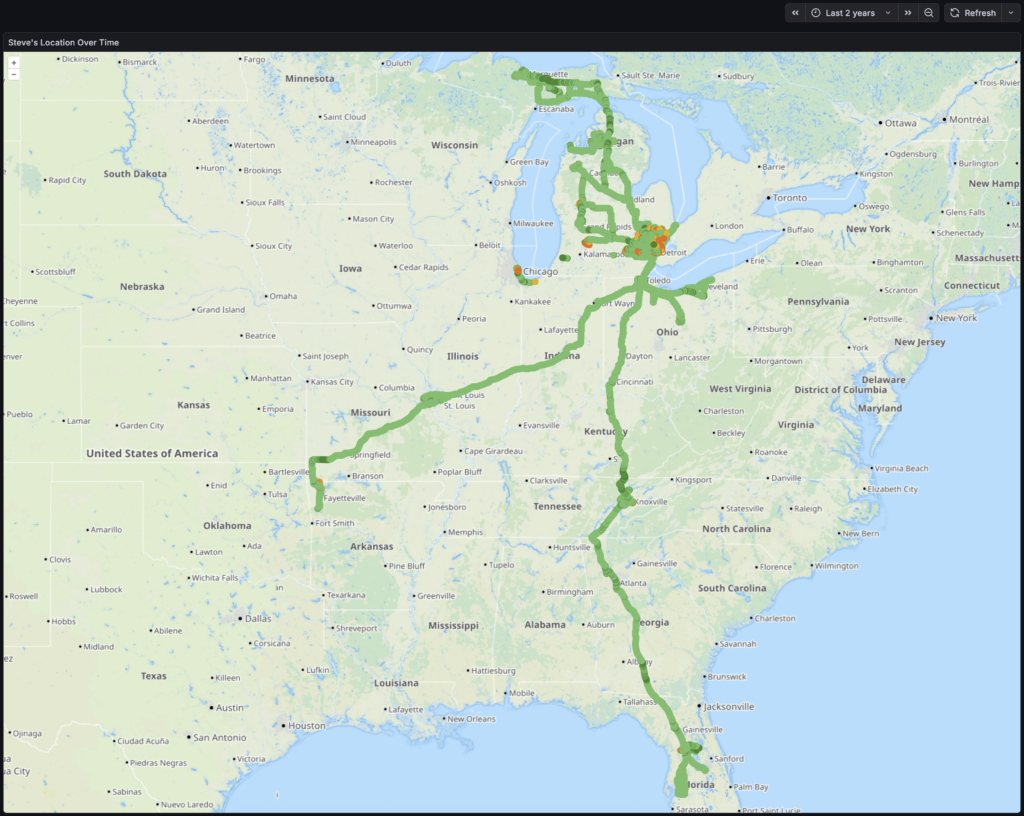

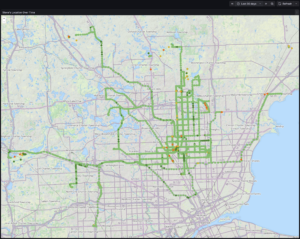

Late on Christmas evening, wanting some time to just sit alone and do things, I put together a map showing where my phone had been. I’m pretty happy with how it came out, as I can now input a time range and dots will appear for each logged location, color-coded with geopositioning accuracy (brighter green is more accurate).

I also used this as another exercise in working with LLM tools like ChatGPT. I’m (finally?) realizing how useful this can be when thought of as a modern search engine. There’s still constant reminders of how imperfect and problematic results can be, but with a domain background it’s helpful. I find that thinking of these tools as tireless (yet emotionless) junior employee who makes lots of mistakes and needs all responses tested and vetted works… decently… in pointing me in a decent direction.

But I digress… Here’s the query that’s the main point of this and makes it all go:

SELECT "latitude", "longitude","gps_accuracy"

FROM "homeassistant"."autogen"."state"

WHERE "entity_id" = 'pixel_8'

AND $timeFilter

AND "gps_accuracy" < 100It was then simply a matter of putting this into a Geomap that displays a point for each location, and colors it based on gps_accuracy state and looks decent. I was even able to place it all on the Thunderforest Landscape map tiles which shows OSM-mapped trails and has been oh-so-useful on my RAMBA Trails Map.

Initially I looked at a heat map, but it didn’t seem as useful as individual points. I may explore this later, but the device where I’m currently running HA is a bit under-powered for this. And note that the query above excludes records that have a GNSS accuracy worse than 100 meters as this generally means that GPS (et al) wasn’t working at all and geopositioning likely came from local mobile towers (which shows me as being on tall local buildings, in fields I’d never visit, etc).

While obvious in retrospect, the most notable things this shows me is that when I’m driving — typically running OsmAnd+ or Google Maps (or both) — the recorded points are high accuracy and frequent. When riding my bike, carrying my phone idly in a pocket, the GNSS sensor is likely PRIORITY_PASSIVE so the dots are both infrequent and low accuracy.

It’s also just neat to look at. Things jump out like a trip to IKEA in Canton, riding at Island Lake and Holly Wilderness, etc.

I’m curious to see what I can further tease out of the logged data. The HA Companion mobile app can get all sorts of interesting info via its Sensors. For example, the Activity Sensors on iOS automatically detect:

- Stationary

- Walking

- Running

- Automotive

- Cycling

And on Android:

- in_vehicle

- on_bicycle

- on_foot

- running

- still

- tilting

- walking

Plus there’s things like what’s being done with the device, what’s seen about its environment (including visible wireless networks, Bluetooth devices), etc…

It might be neat to see what more I can get out of this. Or it might just end up as a nudge to decrease what HA is collecting (and possibly purge some of it from the db).

Of course, it pales in comparison to what the telcos, device manufacturers, OS vendors, and app vendors can do with their data engineers, massive troves of data and ability to cross-reference, etc. (A bit of a reminder that phones are just behavior-trackers that also make calls and take pictures…)

I hope to soon try migrating this HA instance from a Raspberry Pi 4B to a higher-powered slim PC. While I don’t intend to take this much further, it will provide more power for chewing on data like this and will hopefully let me figure out a disaster recovery plan for HA that includes preserving all logged data. When first setting up this map I tried to draw both a location and heatmap and this was a little too much for the Pi and as it ground to a halt Kristen noticed that the back yard lights weren’t turning on properly. Doh! Or I guess I could just do the processing on another machine…

Comments closed